Author: Dilini Algama

Source: The Nation

It took a young actress being told to stay home by her parents for having an affair with one of the violinists for Kaushalya Fernando to star in her first role. An unceremonious, if a trifle amusing entrance has come a long way. It earned her the Best Actress award a record five times. The daughter of Somalatha Subasinghe, Kaushalya easily slips into Sinhala and English as she recounts her naughty childhood, of looking for ‘adventure’ and nearly drowning, her strong mother and her exciting career in acting

By Dilini Algama

Q: What was your childhood like?

A: I had a very nice childhood. I have one sister. I was very close to my grandparents who were from Veyangoda. They were teachers and I loved this village atmosphere and my relatives who came from the village, teachers again. And where my mother lives now, my father bought the land in the 1969 and my father built the house in 1972 or so and this was a real marshy land, a swamp really. It flooded when it rained and there were only a few houses. When it flooded all us children stayed at home and had a real carnival time with paru. We would read those Enid Blyton stories and run around looking for things like islands [laughs]. Once we all jumped on this bed of grass that was on water. We sank and our mothers really spanked us that day. I was always on trees. Our amma had a time with me. I had a nice childhood where I did all assorts of things. Even my parents thought that studying is not about being buried in books.

My father was in transferable service. He was a civil servant. As soon as I was born I was taken to Galle they say and then we were in Mathugama, Nittambuwa, a place called Gurudala, but by the time it was time for me to school we had settled in Colombo. Initially I went to three schools. I was at Anula College, Gothami Balika Vidyalaya and Sujatha College. Sujatha College was in Queen’s Road, Bambalapitiya and it was formed by one Ms. Motwani who was at Visaka Vidyala as well as Musaeus College. My mother was in Museaus College and she’s the person who brought out my mother’s talents. She’s the one who discovered my mother at a time when teachers were rough at her sometimes. My mother had been very naughty, punished outside the class all the time (laughs). Ms. Motwani saw something unique in my mother. That is why my mother was keen to put us to that school. From grade 4 or 5 I was at Museaus College. Really the system and environment of the school was child oriented. Education was not confined to books. They really did concentrate on building up the child. It was all about discovering a child’s talents and developing them. During this time, when I was in grade 4 I realised I could write and direct. Even then I used to write and direct my own plays. It was due to that support and the encouragement I mentioned. When I went to grade 6 that was the time they had subjects like leatherwork, pottery and subjects like that. In that school they had only one or two of these, sewing and home science and my mother thought I could learn them anywhere. The other thing was that it was mainly attended by students of a particular class and my mother thought that I should have the opportunity of associating with people from all walks of life. That’s the outlook my parents had towards society.

My father was in transferable service. He was a civil servant. As soon as I was born I was taken to Galle they say and then we were in Mathugama, Nittambuwa, a place called Gurudala, but by the time it was time for me to school we had settled in Colombo. Initially I went to three schools. I was at Anula College, Gothami Balika Vidyalaya and Sujatha College. Sujatha College was in Queen’s Road, Bambalapitiya and it was formed by one Ms. Motwani who was at Visaka Vidyala as well as Musaeus College. My mother was in Museaus College and she’s the person who brought out my mother’s talents. She’s the one who discovered my mother at a time when teachers were rough at her sometimes. My mother had been very naughty, punished outside the class all the time (laughs). Ms. Motwani saw something unique in my mother. That is why my mother was keen to put us to that school. From grade 4 or 5 I was at Museaus College. Really the system and environment of the school was child oriented. Education was not confined to books. They really did concentrate on building up the child. It was all about discovering a child’s talents and developing them. During this time, when I was in grade 4 I realised I could write and direct. Even then I used to write and direct my own plays. It was due to that support and the encouragement I mentioned. When I went to grade 6 that was the time they had subjects like leatherwork, pottery and subjects like that. In that school they had only one or two of these, sewing and home science and my mother thought I could learn them anywhere. The other thing was that it was mainly attended by students of a particular class and my mother thought that I should have the opportunity of associating with people from all walks of life. That’s the outlook my parents had towards society.

Then I went to St. Paul’s Convent, a government school. You had children from all religions and various walks of life.

Q: Were you as naughty as your mother?

A: Yes, I was really really naughty. I was in the craziest crowd and the teachers thought we were a lot of ruffians and they neglected us to a certain extent. When I went to St. Paul’s Convent the knack that I had towards aesthetics came to a standstill because they were always talking of studies and getting grades. I was put into this class for children who had got through the scholarship exam. There were special classes for them. There was a real competition between the students. Then actually all my writing came to a standstill and I was really disappointed because the environment was so different. Earlier I was in a class of only twenty students. Here there were more than fifty. Gradually I got used to it and I was a person who could get adjusted to any situation. I became more of a sportswoman.My father liked it. He had been quite into sports and he used to train me and I used to get marks for my house and go for district meets. Then I did studies as well because I was determined to go to university. My friends were very intelligent, but they were a bunch of naughty kids. My mother was a teacher and she was teaching at various places and she got herself transferred to my school which I didn’t like at all. The teachers used to complain to her and say, if you don’t do something about Kaushalya she’s going to ruin her life. But amma never said don’t. She just said, “I was worse, let her enjoy her life.” She supported me and when I did my O/Ls I got practically eight distinctions and then my principal was Barbara Gunasekara. She was a very nice lady. She wasn’t that kind where she comes with a cane or anything you know. It was the teachers who were more strict. It was better to be taken to the principal. She was a sweet lady. She said I must do science. My mother had to specially go and say “No Gunasekara I don’t think Kaushalya could sit and study like that because she’s not that way inclined.” Then amma asked me if I could sit and study. She said that if I were to do science I would have to become a doctor and to study I would have to stop seeing theatre and asked if I was ready for it. Then I said no, I can’t stop seeing films and all that. Then amma said okay, you had better do humanities. The principal and teachers were very angry with my mother and they thought that she was crazy, even my relatives thought so. That is why she did this play Vikurthi. It’s through all the experiences she got when I went through education and when she met other friends of mine. She put all this together.

Q: What are the plays and films have you acted in so far? How did you start acting?

A: How I started acting was after O/Ls and till we got our results I was at home. Our mother had this theatre group she to produced theatre for children. She interviewed and auditioned young children and she formed productions with them. There I was like the tea girl, carrying tea for everyone, washing and ironing costumes, I was not into acting or anything. I also did prompting, stage management. One day they were rehearsing and one girl who was a very good singer was stopped by her parents because she was having an affair with a violinist from the orchestra. Then I stepped in and said okay I’ll try. It was a solo narration and like that I first started with the chorus. Little by little when somebody was missing I would do supporting roles. Then amma produced this play called Vikurthi. In that I had a minor role. The gradually when people saw me, like Sugathadasa de Silva this famous, veteran theatre director and he wanted me for his new production called Mara Saal. He cast me in that and that’s how I got into the mainstream. I have worked with people like Dharmasiri Wickramanayake, I acted in two of my mother’s productions, K. B. Herath and Pemasiri Kemadasa and that’s how I got in to theatre.

Asoka Handgama was doing stage productions those days and he also did teledramas. I acted in Dunhinda Addara. Gradually I came in to the teledrama scene, but I haven’t acted in many of them. I concentrated more on stage and I was more interested in studies. I wanted to pursue my studies in drama and theatre, but in Sri Lanka there wasn’t the scope for that. While I was at the University of Colombo we had this real unfortunate situation where it was closed for about three years when I was in my final year.

My parents thought they would never reopen and they sent me to India which I didn’t like. I didn’t like the university and I came back. I was really depressed. In 1990 the university reopened and they had the final exam. On the final day Prof. Siromi Fernando called me to her office and asked if I would like to join the department as a trainee English instructor. I said I’d love to.

What she thought was because I had this theatre background I would be able to move well with the students and be a good teacher. Then I gradually started pursuing how to become a good English instructor and I did a postgraduate diploma in English language teaching. Apart from that I was pursuing my acting, drama and I used to travel abroad a lot to see plays.

Then my mother had this institution and to train actors I had to support her and I was involved in her productions for children. Then Asoka Handagama was looking for someone to play a role in his film Sanda Dadayama and a person called Somapala Hewakapuge had suggested me. That’s how I came into films. Then I acted in Satyajit Maitipe’s Boradiya Pokuna. Then I acted in Vimukthi Jayasundara’s Sulanga Enu Pinisa and I’m also there in his latest film. Then there was Prasanna Vithanage’s Akasa Kusum. Then Bennet Ratnayaka did a new film called Ira Handa Yata.

Q: The role you play in Akasa Kusum was originally meant for Damayanthi Fonseka and the director of the film is Prasanna Vithanage, her husband. When Damayanthi Fonseka refused to play you were cast for it?

A: I didn’t know it was given to her. This happened last year and I had my kids after 11 years of marriage. I was just getting busy with Vimukthi’s film and Prasanna Vithanage called and asked what I feel about acting in a film and I said I’d love to do a film with him. I asked when he was going to start shooting and he said he was shooting the same film he had been doing for some time. I thought he had already finished shooting it. Then he said it was being shot in three parts and I was to act in the third shooting. He said the character was to be played by Damayanthi and that she didn’t want to play it now. I said that if things were okay with him and Damayanthi, I mean it’s his wife no, if it was okay by both of them that I wouldn’t mind.

Q: What do you look for in a role to accept it?

A: I don’t know… I generally like to play tragic characters going through trauma. I think I can play them also more than being very flowery or happy. I think I may not do very well with them, but I haven’t tried them either because I’m normally a happy-go-lucky kind of person. I like to indulge in pain. I also feel a lot. I feel for people in pain and it becomes my problem. From my school days my parents were having a time with me because whenever a friend was ill or something I used to be on the phone calling and helping her and my parents were really angry about it. From school days up to now still I’m the ombudsman of my friends. I always have to listen to their stories and I support them and you know… I don’t know if that’s why I prefer to do this kind of role. And people who come to me do come with roles that they know I’d like to play.

Prasanna Vithanage is a wonderful person to work with. He knows exactly what he wants and how to tell it to his actors. I also liked working opposite Malini Fonseka.

Q: What do you feel about the impeding ban on adults only films?

A: It has been resolved because all the directors went to meet thePresident and they had a discussion and it’s not for Sri Lankan art films. They say it’s a misinterpretation. The ban is for imports.

Q: Tell me something about your family?

A: My husband Dr. Chandana Aluthge is working at the University of Colombo at the Department of Economics. He is the Student Coordinator. He is also a theatre person. He has been working with my mother since he left school and he has a very good sense of art, specially music, theatre, dance. He’s a good choreographer, lighting person, he has a knack for all those things. But then he studied economics as well. He did his PhD in the Netherlands. We have two kids, Haimi and Hans. They are two years and three months old, a girl and boy.

Q: What work are you involved in right now?

A: I did a theatre workshop for young people for about six months and one of the components was writing scripts. We have our own theatre group in our organisation. We have this young scriptwriter called Namal Jayasinghe. He acted in Machang and Ira Mediyama. He has developed three short plays and now we’re going to produce it. Again I’m working with child soldiers at Ambepussa. My mother was requested by the Kadirgamar Foundation, but she isn’t here and I undertook the project.

Q: You also teach drama?

A: Yes, actually at the university I was on the permanent staff at the English Language Teaching Unit and I left in 1999. Then I was doing visiting work for the University of Jayawardanapura. Now at the moment I don’t lecture drama and theatre at institutions, but I work on my own. Also, we do classes for drama activity for children. My husband and I are both involved in that. I do casting for people, unofficially, various things like training. Then friends do plays and want you to come and look at them. Also I teach English by force to my young theatre colleagues [laughs].

Q: What about your years at university?

A: I was at the University of Colombo. It was very nice and I had a bunch of friends. Even yesterday a few of us met at a friend’s house because some had come from abroad. It was nice to meet and talk about our university days. There were also problems at university. At that time my father was the Security Commissioner or someone like that. Some boys suspected that I give news to him. And one day they blocked us inside the canteen, closed up all the doors and gave this speech on knowing whose parents work where and of knowing who tells what to whom. Then we were going to have our final exam and they said we shouldn’t sit for it. But a bunch of my friends did go and sit for it. Two guys carrying two hand grenades down towards Dehiwala died when they blasted in their hands. Later they found a list of names on them and my friends’ names were there. There were many fights at university. Suddenly you’d see a big eruption and you’d see people stabbing each other with broken bottles, nothing like this normal hitting with hands. It was like that so, but even with all this I was in the DRAMSOC.

Q: You don’t mind acting in adults only films?

A: Actually the name adults only is so ridiculous. It’s about life you know. In life there are certain things that you don’t tell anybody that you do. They are very personal things. That doesn’t mean that it’s for adults and such. I think it’s for human beings to reenact and redo. It’s okay to say ‘adults only’ so that the people would know not to take their children because our society is very family-oriented. But that doesn’t mean that a film is going to be something nasty. An actor playing life going to that extent, some people have issues with that. Some look down upon actors. Even within the industry it’s like that. I mean, an actor is an actor, a doctor is a doctor. If a girl becomes a doctor she would have to study the male body, she would have to handle male bodies. But nobody looks down upon them. It’s a profession. Because of actors, people are entertained in one way and on the other hand they can see life through other people.

Q: What you’re involved in is what other people resort to as a leisure activity, so what are your hobbies?

A: I love reading. I really like fiction. At the moment I’m reading Haruki Murakami. I read Orhan Pamuk, a Turkish writer. I like Garcia Marquez and I’ve been reading some good Indian stuff the last few days. Recently I got hold of a book of Kafka’s poems that had lots of poems and I love to read novels. I like to read fiction than even fiction. Then whenever I get to know of films that are out of books, I tend to read them also. I like watching films as well, but I haven’t done much of it since the kids came along.

Play House - Kotte, the leading Children’s theatre, presents a two day Theatre Festival for the young Audiences on December 5 and 6, 2008, at the Lionel Wendt at 3.30 p.m. and 6.30 p.m respectively. The theatre’s latest creation ‘Walas Pawula’ (The Bears and Goldilocks) as well as the well received Punchi Apata Den Therei (We Know It Now) and “Toppi Welenda” (The Hat Seller) will be showcased on these days.. The festival is sponsored by the HNB Assurance PLC (for the third consecutive year) to promote Children’s Theatre in Sri Lanka and thereby contribute to the well being of the country’s future generation.

Play House - Kotte, the leading Children’s theatre, presents a two day Theatre Festival for the young Audiences on December 5 and 6, 2008, at the Lionel Wendt at 3.30 p.m. and 6.30 p.m respectively. The theatre’s latest creation ‘Walas Pawula’ (The Bears and Goldilocks) as well as the well received Punchi Apata Den Therei (We Know It Now) and “Toppi Welenda” (The Hat Seller) will be showcased on these days.. The festival is sponsored by the HNB Assurance PLC (for the third consecutive year) to promote Children’s Theatre in Sri Lanka and thereby contribute to the well being of the country’s future generation.

However, only a handful of these creations have been aimed at children who are considered as the future of the country, requiring proper nurturing and guidance through high quality artistic material.

However, only a handful of these creations have been aimed at children who are considered as the future of the country, requiring proper nurturing and guidance through high quality artistic material.  We forget that children do what they see, hear, and observe in society. Therefore, society has a responsibility in making a good generation of children without inculcating bad values and morals, and also anger, hatred and jealousy in them.”

We forget that children do what they see, hear, and observe in society. Therefore, society has a responsibility in making a good generation of children without inculcating bad values and morals, and also anger, hatred and jealousy in them.”

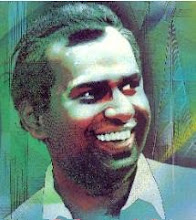

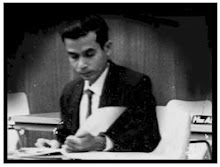

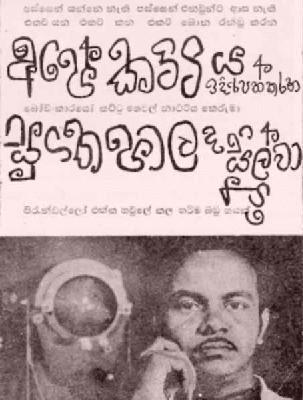

The young Sugathapala de Silva

The young Sugathapala de Silva Sugathapala de Silva: Optimistic about the future of Sinhala drama

Sugathapala de Silva: Optimistic about the future of Sinhala drama සිංහල නාට්ය කලාව සුපුෂ්පිත කොට සුපෝෂණය කිරීම සඳහා බටහිර සම්භාව්ය නාට්ය කලාව සේවනය කළ සුගත් සිය අසමසම කලා ප්රතිභාවෙන් ද සියුම් ගැඹුරු ප්රඥාවෙන් ද උතුම් මනුෂ්ය ධර්මයෙන් ද පොහොණ වූ අප්රමාණ කලාකරුවෙකි. ඔහු ගේ විස්මිත කලා මෙහෙවර සිංහල නාට්ය, නවකතාව, කවිය මතු නොව ගුවන් විදුලිය ආදි ක්ෂේත්ර ගණනාවක් ඔස්සේ විහිදී ගිය මහා ප්රවාහයකි.

සිංහල නාට්ය කලාව සුපුෂ්පිත කොට සුපෝෂණය කිරීම සඳහා බටහිර සම්භාව්ය නාට්ය කලාව සේවනය කළ සුගත් සිය අසමසම කලා ප්රතිභාවෙන් ද සියුම් ගැඹුරු ප්රඥාවෙන් ද උතුම් මනුෂ්ය ධර්මයෙන් ද පොහොණ වූ අප්රමාණ කලාකරුවෙකි. ඔහු ගේ විස්මිත කලා මෙහෙවර සිංහල නාට්ය, නවකතාව, කවිය මතු නොව ගුවන් විදුලිය ආදි ක්ෂේත්ර ගණනාවක් ඔස්සේ විහිදී ගිය මහා ප්රවාහයකි.