Date:19/06/2011

Source: Sunday Times

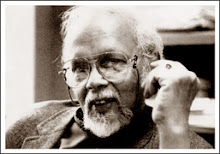

Gamini Haththotuwegama

As the Wayside and Open Theatre group founded by Gamini Haththotuwegama enters its 37th year, Kanchuka Dharmasiri reflects on their incredible journey

On June 6, 1974, a Poson poya day, a group of students and their teacher from the Ranga Shilpa Shalika enacted ‘Raja Dekma, Bosath Dekma’, and ‘Minihekuta Ellila Marenna Berida?’ in a school playground in Anuradhapura. On their way back the next morning, they spontaneously decided to perform on the platform in the Anuradhapura train station for passengers waiting for their trains.

Taking theatre to the people: A scene from a street drama

These incidents mark the defining moments of a group that came to be known as the Wayside and Open Theatre, led for 35 years by Gamini Haththotuwegama until his passing in October 2009. Parakrama Niriella compares the Wayside and Open Theatre to a bus that was moving towards a beautiful infinity in “Prabuddhayana, Andurana, Mithurana”, a piece written as a tribute to Haththotuwegama. Niriella asserts that “the driver of the bus has left it after thirty five years. But the bus is still there and so are the passengers. Now, it is up to them to think about its destination.”

Yes, the bus is moving forward and the group is celebrating their 37th anniversary this year, in fact this month, and is in the process of reviving some of the older plays with the intention of taking them around the country. What is remarkable about this process is that original and former group members such as Nimal Chandrasiri, Jayantha Gunathilaka, Deepani Silva, Nihal Suranji, Saman Hemarathne, and Upali Weerasingha have joined the venture – they are on board again – and are collaborating with current members, Chamaru Pathirana, W.D. Samaranayaka, Veranga Fernando, Sangeetha Abeywardena, Mohan Deshapriya, Roshan Handunnetti, Manoj Indika and many others to reprise some of the plays that were performed in the seventies.

The mid sixties and the early seventies saw an influx of alternative performance groups, motivated by anti-colonial, anti-capitalist, and anti-war movements. While theatres such as the Bread and Puppet Theatre, San Francisco Mime Troupe, the Black Southern Theatre, and El Teatro Campesino were creating radical art in the US, movements such as the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) which began in the 1940s, predating many of the other street and community theatre groups, and Jana Natya Manch (JANAM) formed in India with the intention of creating awareness among people to counter colonial and capitalist onslaughts. Augusto Boal, in Brazil, reconfigured theatre practice by bringing forth his concepts of the theatre of the oppressed in the 60s.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Ngugi wa Miiri collaborated with peasants and workers in an effort to create a people’s theatre in Kamirithu. Similar groups were creating radical theatre in the Philippines and France, and many other countries and this is just a small cross-section of what was happening in the world in terms of political and community theatre movements in the mid twentieth century. It was in such a context and also after an economically and politically tumultuous period in Sri Lanka that the Wayside and Open Theatre formed. Several of these groups have survived, including the Wayside and Open Theatre, and continue to create innovative art that stimulates thinking and encourages a critical outlook on society, politics, and culture.

The Wayside and Open theatre was founded with the distinct aim of taking theatre to the people, those excluded from the mainstream theatre experience in the city centres. Speaking about modern Sinhala theatre that flourished after Ediriweera Sarachchandra’s Maname, Haththotuwegama contends that one of the limitations of the mainstream theatre at the time was its audience: the audience was limited to the bilingual and Sinhala speaking middle classes. In order to counter this inequity, the group took and continues to take theatre to villages, factories, mines, streets, temples, and churches. Their audiences range from peasants, slum dwellers, foreign delegates, passers-by on the streets to university students. Discussing street theatre in an interview with Sunil Mihindukula in 1980 for Silumina, Haththotuwegama explained that the distinct feature about the type of theatre they practise is that it can be performed anywhere, in any form, and in any situation.

G.K: The pioneer

A major aspect of the Wayside and Open Theatre is their refusal to sell tickets, thereby moving away from the trappings of commercial aspects of theatre. In an interview with Birnn Das Sharma in Seagull Theatre Quarterly, Gamini Haththotuwegama claims that “Anyone who wants to see the play must be allowed to see it. There are no tickets. This is very important.” This principle is significant in a world that is becoming increasingly commercialized, where everything is predicated on money, in a context where theatre and other arts are becoming an exclusive activity enjoyed by certain classes, and in a time when the capitalist system is demarcating spaces based on class lines.

One of the main goals of the group thus is to make theatre available to all those who want to see it and go beyond class barriers. The work that started with such intentions in the seventies still goes on and the Wayside and Open Theatre travels all around the country taking theatre to thousands of people. Despite grave hardships, they have managed to sustain themselves as an independent group for more than three decades.

In recent months, the group has started reviving several of their older plays including ‘Minihekuta Ellila Marenna Berida?’, ‘Raja Dekma’, and ‘Pinata Gal Geseema’. ‘Minihekuta Ellila Marenna Berida?’ is the story of a man who is not allowed to even hang himself, or in other words his attempt to hang himself gets constantly postponed in a tragically comic manner, because the wife, the priest, the minister, the writer, the sociologist – members of various social institutions – keep interrupting him.

They are resolved to get the maximum out of him before he hangs himself, and also contemplate ways of profiting from the hanging itself: the wife wants the man to pay numerous bills before he dies, the writer wants to compose a poetic novel about the sentiments of a dying man while the sociologist sees another apt subject for his study. The journalist and the photographer find a media-worthy subject in the story of the man who is about to hang himself and are thrilled by the idea of a sensational news item. No one is able to go beyond the use value of the man and think about him as a human being or even to simply inquire about the reasons for his action. All this time the man is standing on a bench with a noose around his neck!

We have arrived at a point where despair is even profitable! Another play that the group has been working on restaging is ‘Raja Dekma’, a piece based on the emperor who walked naked. They have also been rehearsing ‘Pinata Gal Geseema’, a short improvisational piece that addresses sentiments related to guilt and judgment. In their more recent work such as ‘Dead Mobiles’, the group comments on the cellular phone invasion that has invaded the lives of millions in Sri Lanka and the world. Absorbed in their incessant phone chatter, the characters fail to notice the cry of a dying man. Has the idea of communication so utterly changed in the modern world we live in?

The group also performs Ammata Undata, a lyrical composition written in a language that is very subtle and vivid. In the play, several characters sit around in a circle and tell stories about their day and life. Intermittently a doctor enters and asks them to show their tongues and hands, but there is no indication as to where the action takes place precisely.

Through the brief moments in which the characters recount their lives and experiences, we are given a glimpse to a larger part of their lives. One character utters: “my mother’s hands are very soft, very beautiful. They got broken by working for us. Pau (sin). Well, what are mothers there for, but to work! Pau.” With precise timing and delivery these few lines comment on the horrors of a patriarchal system. This is a rare play of the group in which allusions are made to the place of women in society and how gender operates in what is predominately a male-centred world.

Perhaps taking such works as a starting point, one hopes that the future of Wayside and Open Theatre will involve more substantial and complex roles for the female members and move beyond those that are outdated clichés of female stereotypes.

As Ammata Undata continues, various characters offer entirely different vignettes from their lived experiences. One of the characters claims, “I don’t lie more than 45 times a day. It’s true; I’m not lying. Small lies don’t count here, ok? I managed to get my little ones admitted to school by lying.” The beginning of the sentence seems comic, but when the character mentions how he had to lie in order to procure a good education for his child, layers of criticism regarding the school system and the social system are brought to the fore. Many works of the Wayside and Open theatre group manage to create meanings that interact and intersect at several levels.

Group members continue to hold workshops every week and train new actors. They will be starting a new workshop in July. A website of the Wayside and Open Theatre is well underway. This is a significant year for the group as they continue their mission of taking theatre to the people. What an incredible journey…