Source : Sunday Observer

Date:03/Nov/2002

|

|

The death of Sugathapala de Silva last Monday at the age of 74 after a long illness evokes a sense of epochal loss. For if Ediriweera Sarachchandra gave the Sinhala theatre a local habitation and a name by taking it to its roots in folk drama Sugath as everybody knew him, accomplished the next task of bringing the new theatre to the audiences of the 1960's. It has been said of the Russian novel that it emerged from Nikolai Gogol's 'Great Coat.' In the same sense all serious Sinhala drama of today has emerged from Sugathadasa de Silva's womb although he may not have fathered them himself.

Dissatisfied with his own translations and adaptations of the plays of Moliere, Gogol and Chekhov (done in collaboration with E.F.C. Ludowyke and A.P. Gunaratne) Sarachchandra after studying the Japanese folk theatre turned to our own nadagam, kolam and sokari plays and the thovil ceremonies to seek the roots of an indigenous theatre which would evoke a resonance from the soul of a people only recently liberated from the imperial yoke. The fruit of this labour was, of course, 'Maname' his refined adaptation to the stage of the original nadagama as enacted by Charles Silva Gunasinghe Gurunnanse of Balapitiya.

|

|

He reached the apogee of these labours with 'Sinhabahu', his own play where with skilful stylised movements, memorable poetry and haunting music he was able to narrate the story of the origin of the Sinhala race and suggest through it a contemporaneous generational gap. But by the early 1960's the stylised form had spawned mindless imitators who had made a caricature of Sarachchandra's mode. What is more, there was the feeling that the mode had exhausted itself and it was this new thinking which Sugath's generation represented. This was a generation of bi-lingual youth either of urban origin or who had come to Colombo in search of the pot of gold at the foot of the rainbow. They were a middle class generation working in newspapers or the advertising industry.

They were also excited by the new trends in English literature, drama and the cinema. Most of them were grouped round the 'Sinhala Jathiya' paper (published by Gilbert Perera of the Perera and Sons family) and the magazine 'Dina Dina' edited by Anandatissa de Alwis. The late Cyril B. Perera recalls in a tribute to Neil I. Perera how of a Sunday, Neil would somehow find the money to watch a film with a couple of friends to the accompaniment of a few bottles of beer, a packet of kaju and a packet of Bristol cigarettes! Basically outsiders to the Big City these young men would chase the sun down into the sea with their conversation which centred on bringing about an awakening in the arts.

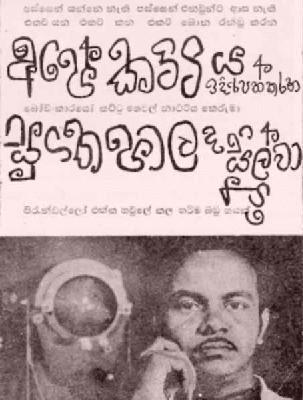

It was out of these conversations that the idea of forming 'Apey Kattiya' emerged. Established as a loose artistic grouping at the now extinct Indian Club in Kollupitiya it took the Sinhala theatre by storm with such plays as 'Boarding Karayo' and 'Thattu Geval.' But it was not confined to drama alone. Sugath himself brought out several novels during this time such as 'Asuru Nikaya' and 'Biththi Hathara' later made into a film by Parakrama de Silva.

Sugath was no doubt inspired by dramatists such as Tennesse Williams and Pirandello translating or adapting successively their 'Cat On a Hot Tin Roof' and 'Six Characters in Search of an Author' but there was no doubt that he was a natural dramatist wishing to break through the mould of the proscenium arch. Technique which he used at the time such as a character running up on stage through the audience were revolutionary for their times and was like a whirlwind blowing through the claustrophobic corridors of the Sinhala theatre as well as ossified middle-class manners and morals.

This was a personification of the aspirations, satisfactions and frustrations of a new urbanised generation which was burgeoning in the 1960's.

But if in the 1960's Sugath expressed an existentialist sense of alienation, by the 1970's he had become a more overt politically inclined dramatist and writer. By this I do not mean that he ever waved a party flag or fell victim to the wave of socialist realism which swept the arts sometimes in deference to the new United Front regime led by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike in 1970. Sugath was too percipient a writer for that. In fact there is no other artist in Sri Lanka (With the exception perhaps of Gunadasa Kapuge) who has been so battered by the bludgeon of blind political power as Sugath. However Sugathapala de Silva never fell into the intellectual error of confusing personal political convictions (which he firmly held) with partisan party politics.

His best play will perhaps remain 'Dunna Dunu Gamuwe' which was made in the aftermath of the 1971 Insurrection. Although centred on a trade union struggle (which might have looked like small beer to the brave insurrectionists) it had an admixture of politics and art expertly mixed with technique and aided by some superb acting by the late U. Ariyawimal and W. Jayasiri was the percussor of the serious political theatre which followed at the end of the decade.

In that sense Sugathapala de Silva will remain the one bridge which brought together the realistic theatre of the 1960's with the absurdist theatre of the 1970's and the post-modernist theatre which followed. Whether it is Simon Navagaththegama, Parakrama Niriella, Dharmasiri Bandaranayake or the latest star Rajitha Dissanayake all of them owe their origins to Sugath. Some may have followed his politics and others his techniques and some a mixture of both but the debt is beyond doubt and will certainly not be challenged.

Born in Nawalapitiya, the son of a small trader, Sugath grew up in that peculiar milieu of small town commerce with its mix of Sinhala, Tamil and Muslim traders. He has portrayed these experiences of Colombo and Nawalapitiya in different ways in the novels 'Ballo Bath Kathi,' 'Ikbithi Siyalloma Sathutin Jeevathvuha' and 'Esewenam Minisune Me Asaw' which were peculiar political novels in their own ways. Here we see the agonies and ecstasies of a newly-arrived class, their gradual evolution into a national bourgeoisie and finally their bid to challenge and even dialodge the old comprador class. As a political novelist Sugath was no propagandist and was too subtle a writer to make overt political statements but all his work is shot through with his sense of immense humanism and his hope for a better society for the wretched of the Sri Lankan earth.

A self-made man Sugath was widely read and belonged to a class of self-reliant and self-supporting artistes who are now extinct in the country.

Even though politically battered, economically derelict and at times his family itself scattered he never gave up hope or went behind the patronage of politicians. Even though bed-ridden for the last several years he did important translations the last being Shyam Selvadurai's 'Funny Boy' which was released only last month.

This showed his readiness to keep up with the young and the latest in literature and ideas even in the seventh decade of a crowded life.

Sugath worked for long at the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation as a producer and in the late 1960's was in charge of the weekly radio drama and the weekly short story programs which were the first stamping grounds of writers and dramatists who are today well-known in their own right. But he himself led no school or cult and 'Apey Kattiya' was a loose democratic organisation with no formal structure although he was certainly its undisputed leader or the 'Loveable Dictator' as he sought to describe the role of the director in the theatre.

In both the theatre and literature Sugath can be seen as an early percussor of post-modernism, a much abused term today. One of his earliest novels 'Asura Nikaya' was a depiction of the silver screen of the 1950's and 1960's when stars were worshipped as gods and goddesses. 'Biththi Hathara' was about the aimless life of a philandering young man adrift in the heartless city. In 'Hitler Ella Marai' he re-created the life of Adolph Hitler in his own idiosyncratic manner.

Sugathapala de Silva was almost the last of a generation. This was a time when Government servants like Henry Jayasena, S. Karunaratne, Sugathapala Senarath Yapa, R.R. Samarakone, Sandun Wijesiri and Dharmasiri Bandaranayake (to name only a few which presently come to mind) were active in the theatre and the cinema although receiving no duty leave for these cultural activities.

The cost of living was reasonable and a middle-class family could go to the theatre or the cinema without much strain on the family budget. Buses ran late into the night so that they could go back home. The Lumbini and the Lionel Wendt theatre were hives of activity before the Centre could not hol d any more.

d any more.

Today, however, we live in the electronic age which some call progress but where much of the decencies of life have been lost. Sugath himself was a victim of this decay and death of decency but watched it all with a philosophic detachment from his sick-bed in a ground floor Moratuwa Soysapura scheme flat.

Many of the luminaries of 'Apey Kattiya' such as Cyril B. Perera, Neil I. Perera, Augustus Vinayagaratnam and G.W. Surendra went before him. He follows them bringing down the curtain not only on a full and chequered life but also a cultural era in our troubled country.

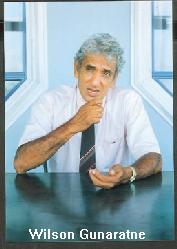

The young Sugathapala de Silva

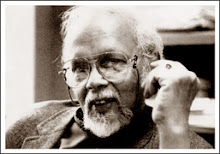

The young Sugathapala de Silva Sugathapala de Silva: Optimistic about the future of Sinhala drama

Sugathapala de Silva: Optimistic about the future of Sinhala drama සිංහල නාට්ය කලාව සුපුෂ්පිත කොට සුපෝෂණය කිරීම සඳහා බටහිර සම්භාව්ය නාට්ය කලාව සේවනය කළ සුගත් සිය අසමසම කලා ප්රතිභාවෙන් ද සියුම් ගැඹුරු ප්රඥාවෙන් ද උතුම් මනුෂ්ය ධර්මයෙන් ද පොහොණ වූ අප්රමාණ කලාකරුවෙකි. ඔහු ගේ විස්මිත කලා මෙහෙවර සිංහල නාට්ය, නවකතාව, කවිය මතු නොව ගුවන් විදුලිය ආදි ක්ෂේත්ර ගණනාවක් ඔස්සේ විහිදී ගිය මහා ප්රවාහයකි.

සිංහල නාට්ය කලාව සුපුෂ්පිත කොට සුපෝෂණය කිරීම සඳහා බටහිර සම්භාව්ය නාට්ය කලාව සේවනය කළ සුගත් සිය අසමසම කලා ප්රතිභාවෙන් ද සියුම් ගැඹුරු ප්රඥාවෙන් ද උතුම් මනුෂ්ය ධර්මයෙන් ද පොහොණ වූ අප්රමාණ කලාකරුවෙකි. ඔහු ගේ විස්මිත කලා මෙහෙවර සිංහල නාට්ය, නවකතාව, කවිය මතු නොව ගුවන් විදුලිය ආදි ක්ෂේත්ර ගණනාවක් ඔස්සේ විහිදී ගිය මහා ප්රවාහයකි.

'In western countries the actors are given a chance to play more than a single character. But in Sri Lanka it is not a common practice. Once Shivaji Ganeshan acted nine characters in 'Nawa Raathri'. That was a film and nobody has done anything more than double acting in local films', Wilson said.

'In western countries the actors are given a chance to play more than a single character. But in Sri Lanka it is not a common practice. Once Shivaji Ganeshan acted nine characters in 'Nawa Raathri'. That was a film and nobody has done anything more than double acting in local films', Wilson said.