In the decades after Independence, Sinhala drama, which was once relegated to the periphery of cultural life, emerged into the spotlight as a vibrant mode of artistic expression.

Author:A.J. GUNAWARDENA

Source:Frontline Date: 13 - 26, 1999

SINHALA drama, in common with most other contemporary art forms of Sri Lanka, occupies a bipolar universe characterised by a complex set of tensions and associations occurring between the traditional and the modern, the indigenous and the foreign, or in a Tagorean phrase, between the home and the world. This situation is in large measure the product of certain features that are peculiar to the culture and to the historical circumstances surrounding them. Among these, the most important factor has been the relatively low social status accorded to mimetic and performative arts. Sinhala literature, which has a distinguished tradition going back to early medieval times, eschewed drama altogether. Until almost the beginning of this century, the theatrical arts were confined to the folk domain. And since folk theatre was tied to single texts or a cluster of specific texts concerning myth and legend, dramatic writing remained a virtually unknown craft in Sinhala society.

This situation changed marginally during the latter half of the 18th century with the emergence of a form of theatre known as nadagam. A folk theatre strongly influenced by the Catholic Church, and originally dedicated to the enactment of biblical tales, nadagam progressively turned into a vehicle of popular entertainment divorced from liturgical texts. It thus created a demand for new texts, and the habit of dramatic composition, albeit at a rather crude level, came into being. Writing for nadagam, however, never left the folk stratum.

The arrival of Parsi or 'company' theatre in the penultimate decade of the 19th century marked a major turning point in the history of Sinhala drama. Known in Sinhala as nurti, the Parsi theatre captured audiences in much the same way that another Mumbai product - the Hindi film - was to do several decades later. Nurti was a form of entertainment the likes of which had not been witnessed in the country before. It offered action, costume, song, dance, colour, magic, spectacle - a conflation that proved an immediate hit with the urban, educated Sinhala public as well as with the working classes.

Nurti, an ungainly hybrid with little to recommend it artistically, had a long-lasting impact on Sinhala culture. Its captivating melodies invigorated the process that led to the adoption of the North Indian ragadhari school as their classical music discipline by the Sinhala people. At the same time, nurti also initiated and promoted the activity of formal dramatic composition in the Sinhala language, for the commercial stage had to be fed with new plays.

The pieces written for the nurti stage by Sinhala writers reflected the ethos of the times. Although never openly anti-British, or contemporary in character and situation, these plays gave voice to the rising chorus of nationalist sentiment. The playwrights recalled a glorious past and rallied the people against alien habits and values. Despite its popularity - or rather because of it - nurti was unable to develop into a mature and sinewy dramatic form. An urban-based commercial enterprise, nurti could not survive the challenge of motion pictures, especially that of the products of Mumbai and Chennai. By the 1930s, the curtain had come down on nurti as a regular stage presence. However, the lacuna was filled before long by another species of 'company' theatre - one that followed the basic structure of nurti but dealt with contemporary characters and situations. These plays addressed such social issues as caste and the dowry system, in a manner resembling Hindi and Tamil films.

Once more, however, Sinhala drama was swallowed by film. This time, though, the post-nurti stage establishment volitionally embraced this fate. Beginning in 1947, theatrical professionals gave up the stage altogether and began converting their repertory for the silver screen. (This, incidentally, was how the Sinhala film came into being.) Plays became films, often preserving their inherent theatrical structures. The departure of theatrical personalities and their popular wares to South Indian studios (where the actual conversion was done) spelled the end of the professional Sinhala stage. What took its place, and has been evolving during the 50 years since Independence, is essentially a non-commercial theatre peopled by dedicated amateurs who do not expect to make a living from the stage. Since that time the money and rewards offered by theatre have not sufficed to provide an independent livelihood for its practitioners.

The roots of the Sinhala drama that succeeded the professional stage go back to exercises in translation and adaptation undertaken by the English-educated literati who were inspired by the example of modern Western drama. As in the case of most other Asian countries, there were in Sri Lanka groups of concerned individuals who wished to develop a drama that was both modern and yet accessible to an uninstructed audience. They hoped to achieve this end through the translation and adaptation of suitable Western plays. In Sri Lanka, the choice included Gogol, Chekhov and Moliere.

By the 1950s, this approach appeared to have reached something of a dead end. The modes of realism and naturalism had failed to produce works of substance, and indeed continued to look and sound rather alien to the Sinhala stage. Sinhala drama seemed to have lost all sense of direction and purpose. It was at this point that Ediriweera Sarachchandra, Sri Lanka's greatest playwright, came into the scene.

Sarachchandra, an academic by occupation, was a moderniser who was essentially Tagorean in spirit. Indeed, he had spent some of his formative years at Santiniketan and subscribed to the intercultural philosophy of Tagore. Sarachchandra, convinced that the direct emulation of Western forms was not the way forward for Sinhala drama, sought to attain a viable fusion of the Western and Asian modes. He further believed that drama was a poetic medium which, most properly, should concern itself with perennial themes, and not with quotidian issues. The use of poetry, music, song, dance and stylised gesture on the modern stage was entirely appropriate, he argued.

Sarachchandra's work for the stage followed these principles. Writing and directing the plays himself, he demonstrated outstanding poetic gifts and a sure grasp of modern stagecraft. Always working with 'found material' such as Buddhist Jataka stories and folk tales, he experimented with traditional theatrical forms. For his path-breaking "Maname" (1956), Sarachchandra employed the almost extinct nadagam form. This turned out to be an inspired choice, for the nadagam elegantly accommodated the theatrical vocabulary he favoured.

BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Playwright Ediriweera Sarachchandra. He believed drama was a poetic medium which should concern itself with perennial themes.

Playwright Ediriweera Sarachchandra. He believed drama was a poetic medium which should concern itself with perennial themes.

"Maname" accomplished several objectives. While offering an exceptionally satisfying theatrical experience, the play validated the path that Sarachchandra sought to follow. It demonstrated that a productive fusion of the traditional and the modern was not only feasible on stage but desirable. As a shining example of new possibilities in theatre, "Maname" brought self-esteem and a mood of self-confidence into the sphere of Sinhala theatrical activity.

Over time, however, "Maname" and Sarachchandra's subsequent dramatic output, along with his general philosophy of theatre, generated an adverse critique. It was argued that Sarachchandra's kind of drama and the theatrical conventions he followed could neither reflect the actualities of contemporary society nor articulate thematic concerns of a social and political nature. It was also pointed out that Sarachchandra's preoccupation with so-called 'eternal values' deflected attention from the real and pressing issues of the day. The view was also expressed that the use of song, music and stylised gesture could lead to unwholesome aesthetic indulgence on stage.

The controversy centring on Sarachchandra's dramaturgy split the Sinhala theatre world into two camps. Although it failed to maintain a high level of understanding or historical knowledge, the debate was a necessary exercise - an evolutionary need, as it were - in a medium that was trying to define itself. However acrimonious at times, the exchanges had a salutary effect in the long run. They led to the realisation that drama and theatre do not permit facile categorisations.

Notwithstanding the authoritative role played by Western models in Sinhala drama, the general movement or progression has been towards the consolidation of a presentation or performative mode of theatre as opposed to the representational. Examples of authentic realism are infrequent on the Sinhala stage, and naturalism is practically unknown.

The thematic scope and the performative range of Sinhala drama palpably broadened after the advent of "Maname". From the 1960s onwards, material of a social and political tendency captured much of the theatrical space. The stage spoke loudly and passionately about problems and conflicts thrown up in a society undergoing rapid change on all fronts. Playwrights rode full tilt against the iniquities and injustices of the social order, the hypocrisies and dissemblings of those who sat in places of power, and the general decline of moral and ethical values. The Sinhala stage functioned as a sprightly forum of debate and discussion, moving away from the contemplative and the lyrical and favouring the rhetorical and the dialectical.

BY SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

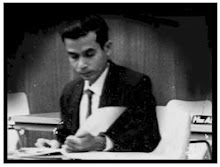

Edmund Wijesinghe as Vedda King and Trilicia Gunawardena as Princess in the first production of Ediriweera Sarachchandra's "Maname" (1956).

Edmund Wijesinghe as Vedda King and Trilicia Gunawardena as Princess in the first production of Ediriweera Sarachchandra's "Maname" (1956).

During the years after "Maname", Sinhala drama enlisted the energies of succeeding generations and established itself as the most exciting and provocative medium of experiment and socio-political utterance in the country. But its artistic growth has hardly kept up the promise of the 1950s. The Sinhala theatre has shown an abundance of individual talent, but weak organisational structures together with the lack of professional commitment have stymied progress. Pre-censorship of texts has also been a discouraging factor for playwrights and producers. Nor has there been a substantial augmentation of the repertoire of plays available for production.

The profile of Sinhala drama changed radically within a decade of Independence. Over the decades, a medium once relegated to the periphery of cultural life emerged into the spotlight as a sinewy and vibrant mode of artistic expression. Two factors lay behind this metamorphosis. One was the confidently affirmative attitude towards traditional arts, which developed in the aftermath of Independence. The other was individual talent. The dissonances between tradition and modernity continue to persist on the Sinhala stage despite its eclectic and liberal approach to the craft. Perhaps these can never be fully resolved, given that drama cannot fail to mirror social and cultural conflict.

A.J. Gunawardena, who died in October 1998, was the Head of the Department of English at Sri Jayawardenapura University and also of the Institute of Aesthetic Studies. He was one of Sri Lanka's leading critics of theatre and film.

Aj Gunewardena wrote extensively on sri lankan drama and films.His criticisms were great and opened the eyes of many to see the works of art from different perspective without demoralising the artists' feelings.

ReplyDelete