Date:14/11/2010

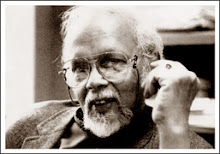

Source: The Sunday Times“That’s the only film of mine that I can sit through today without blushing or wanting to run out” – Basil Wright, director of Song of Ceylon.

Sri Lanka has inspired some notable 20th century artistic masterpieces, from D. H. Lawrence’s poem “Elephant” to Henri Cartier-Bresson’s portfolio of photographs. Then there is Basil Wright’s film Song of Ceylon, one of the finest documentaries ever produced. Made in 1934, it has been assessed - correctly, I think – as the film that has “best projected the image of the country, the soul of its people, and the endless beauty of the landscape with a subtle touch of magic for the world to see and admire.” Indeed, over the decades it has probably done more to publicise the island than any other promotional film.

Basil Wright

Song of Ceylon was one of many outstanding documentaries produced in the 1930s by the Empire Marketing Board Film Unit (later the British GPO Film Unit) as the result of the pioneering vision of one man, John Grierson. In 1929, Grierson had directed the influential film, Drifters, which wasthe first example of what came to be called the British Documentary Movement. In the studio-bound British cinema of the time, a film like Drifters that drew its drama at first hand from real life was revolutionary. Grierson’s simple story of the North Sea herring fishery brought what were then new and startling images to the screen.

Grierson was a brilliant theoretician as well as an accomplished film-maker. It was he who first used the term “documentary” in 1926 in a review of Robert Flaherty’s film, Moana. “Of course, Moana, being a visual account of events in the daily life of a Polynesian youth and his family, has documentary value,” he wrote, later defining the word as “the creative treatment of actuality.” And it was he who developed the documentary movement “to bring alive to the citizen the world in which his citizenship lay, and to bridge the gap between the citizen and his community.”

He believed that the “documentary idea demands no more than that the affairs of our time be brought to the screen in any fashion which strikes the imagination and makes observation a little richer than it was. At one level, the vision may be journalistic; at another, it may rise to poetry and drama. At another level again, its aesthetic quality may lie in the mere lucidity of its exposition.”

What we understand by the word documentary precedes Grierson’s coining of it, for cinema began with documentary material called topicals in which the camera passively observed babies eating breakfast, trains arriving at stations, and workers leaving factories. However, audiences soon grew bored with topicals. They demanded of the new medium what they demanded of the older media - the narrative form. Only when Flaherty began to structure his actuality material so that it might satisfy the needs of audiences could Grierson identify a new type of film and call it documentary.

Instead of directing other films, Grierson devoted his energies to establishing a documentary film unit at the Empire Marketing Board in London. He gathered around him a group of young men – Arthur Elton, Paul Rotha, Harry Watt, Edgar Anstey, and Basil Wright, to name but a few – who were all destined to make their own distinctive contribution to the genre.

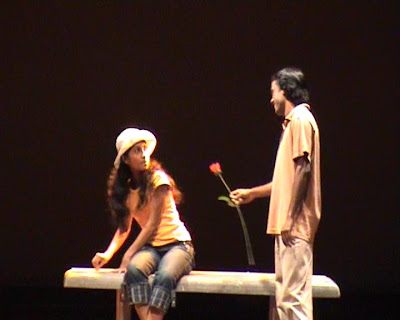

Song of Ceylon was one of many Grierson documentaries made with enlightened sponsorship from industry and government departments – in this instance the Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board, which today goes by the name Sri Lanka Tea Board. Director-cameraman Basil Wright was chosen to direct the four one-reelers that had been commissioned by the board. Wright had started his directorial career with the parochial The Country Comes to Town and O’er Hill and Dale, both made in 1932.

He then went to the Caribbean, where he demonstrated a penchant for exotic locations and developed a symphonic style with his 1933 documentaries Windmill in Barbados and Cargo from Jamaica.

Part of Wright’s distinction as a film-maker was the conscientious manner in which he went about his work. Indeed it was said of him that no director ever travelled to a location better prepared. Before embarking for Ceylon he researched diligently, reading every book on the island he could find. He even visited John Still, who had lived in Ceylon for many years and who was the author of Jungle Tide (1930), one of the best accounts of the wild interior of the island.

The 27-year-old Wright arrived in Colombo with his assistant, John Taylor, on New Year’s Day, 1934. He soon made the first of two important discoveries that were to have a significant influence on the production. It was only natural that Wright was eager to find a Ceylonese to assist him on location, for the first impulse of the film-maker in a strange land is to find someone with the right local knowledge. G. K. Stewart, Chairman of the Ceylon Tea Propaganda Board, suggested Lionel Wendt.

It was an inspired recommendation, as Wendt was Ceylon’s finest still photographer and knew his country intimately. Years later, in 1949, Wright gave an interview for Mosquito, a magazine for Ceylon students in England. “I think he was one of the greatest still photographers that ever lived,” Wright said of Wendt. “I should place him among the six best I’ve come across – including a photographer who had very much to do with Ceylon, Julia Margaret Cameron.”

Wright was staying at the Grand Oriental Hotel in Colombo. One morning Lionel Wendt turned up. According to Wright, the photographer was very much on the defensive at first. “But within five minutes we were both roaring with laughter,” Wright told his interviewers. “He had a wonderful sense of humour.” From the time of this propitious meeting of minds, Wendt played a vital part in the small film unit and accompanied Wright and Taylor almost everywhere they went during the seven-week shoot.

The unit travelled extensively, capturing some of the first documented moving images of the country – though, admittedly, the film archives of the Library of Congress contain two much earlier films, A Ramble through Ceylon (1905) and Curious Scenesin India (1912). Guided by Wendt, the unit climbed Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak), explored the hill country and ruined cities, and witnessed rural life in abundance. Wright filmed fisherman and farmers, Buddhist monks and coconut-pluckers, craftsmen and dancers.

Wright and Taylor returned to England in April 1934 with two well-known Kandyan dancers, Ukkuwa and Gunaya, who had taken part in the film. They were to assist with the post-synchronisation, as no sound had been recorded on location. Later Wendt joined them in London. While the composer Walter Leigh worked on the orchestral score, Wright began the editing. By the time he had completed a rough-cut of the four one-reelers, he understood that together they made a complete documentary.

Grierson invariably made a creative contribution to every film he produced, and Song of Ceylon was no exception. As Wright commented: “You had to get used to doing without sleep and that sort of thing, but he was the most rewarding person to work with that I’ve ever met, because he was able to extract from you abilities which you didn’t know you had but which he sensed. He never told you how to correct your mistakes. He simply told you how damned lazy, intellectually lazy, you were not to develop the theme which you’d taken, in a proper manner.”

On being shown the rough-cut Grierson remarked to Wright: “Absolutely marvellous. Except that there’s something so terrible at the end that you have got to put right.” Grierson was referring to a scene in which a pingo-carrier makes an offering of flowers at Gal Vihara, the statuary complex in the medieval capital of Polonnaruwa. Wright had juxtaposed this reflective scene with an energetic Kandyan dance and they clashed. “It’s a stupidity. It’s a betise,” Grierson told the director. “It doesn’t work.”

By this time Wright had been working on the film for many months. He had become too involved and couldn’t grasp Grierson’s point. Producer and director proceeded to have their only serious difference of opinion during years of creative collaboration – “a bang up and down row” as Wright described it. Afterwards, Wright went home and started to drink. The next day he refused to go to the studios.

The following evening he started to think about the film once again and suddenly had an idea regarding an alternative ending. He drove to the studios after midnight and, as he recalled, “picked up a second take of the man reading that prayer on Sri Pada (which happens at the beginning of the film), chopped it up, and related these phrases to the shots of the men dressing for the dance, which I hadn’t used at all.”

When Grierson arrived at the studios the next morning, Wright was still there. The last reel was duly screened for the producer, who commented when the lights came up: “There, what did I tell you? There’s absolute genius.”

“He was right, and I was right because I found out how to do it,” Wright said of the episode. “Because that scene is vitally important to the film.” It is vitally important. Moreover, the location had personal significance for Wright.

“There are certain small patches of the earth’s surface,” Wright wrote of Gal Vihara in connection with the centenary of Ceylon Tea in 1967, “which have a character and influence so powerful that anyone who stands within their bounds is deeply and intimately affected. One of these – for me at least – is Gal Vihara. Up from the wiry grey-green grass in a treeless precinct juts, like a whale, an enormous outcrop of granite. From this living rock was carved, centuries ago and on a cyclopean scale, a fourfold image of the Buddha.

“If you go nearer to the Gal Vihara and step on to the burning floor of granite in front of the statues, you will see, as often as not, a little round basket containing rice and frangipani. Perhaps it is a pingo-carrier who has been here with his two flat baskets swaying from his shoulder-yoke like a pair of scales. He puts down his burden, unlooses his headwrapping, loosens the fold of his sarong and lays on Buddha’s reclining elbow his humble offering. Then, after bending thrice in prayer, he walks backwards from the sleeping god, hitches up his skirt again, winds the simple white cloth round his head, picks up his load again and, with the swinging rhythmic walk of a yoke-carrier, departs. And when he is gone the sense of scale goes too. With no human figure for comparison, the great carvings are no longer great. They have no need to be enormous, no need to be tiny; they are beyond comparison, beyond consideration, belonging only to the nothingness of absolute peace.”

This is an exact description of the scene from Song of Ceylon - a director’s meticulous evocation of his work a third of a century after the event. One morning alone at Gal Vihara, Wright underwent an experience in which “the backward and forward ripples of my Western mind gradually came to rest, and I was at peace.”

It was while editing that Wright made the second of his important discoveries that influenced the outcome of the film. Although he was familiar with many of the important books about the island, it is curious that he was unaware of Robert Knox’s An Historical Relation of Ceylon (1681). He stumbled on a copy in a bookshop near the British Museum and realised it would provide an ideal commentary for the film. It is apt that passages from the first and finest book in the English language on Ceylon should be used in the first and finest documentary film on the island.

He tried several voices for the narration, but none satisfied him. Just four days before Wendt was due to return to Ceylon, Wright asked him if he could test his voice. Wendt read Knox’s prose in his characteristic voice, described by the Mosquito interviewers’ as “dry, precise and faintly sepulchral.” It was perfect for Wright, and subsequently Wendt recorded the narration for the final version of the film, reading it straight through in a single take.

Song of Ceylon, which is 40 minutes in duration, premiered as a second feature at London’s Curzon Cinema in early 1935. The most eloquent review of the documentary, which is reproduced in Alistair Cooke’s Garbo and the Night Watchmen (), was written by the author Graham Greene. “Song of Ceylon is an example to all directors of perfect construction and the perfect application of montage,” Greene wrote. “Perfection is not a word one cares to use, but from the opening sequence of the Ceylon forest this film moves with the air of absolute certainty in its object and assurance in its method.”

In the first part of the film, called The Buddha, the camera clings to a line of pilgrims ascending Sri Pada. At the summit, “as a priest strikes a bell, Mr Wright uses one of the loveliest visual metaphors I have ever seen on a screen,” continued Greene. “The sounding of the bell startles a bird from its branch and the camera follows the bird’s flight and the notes of the bell across the island, down the mountain side, over forest and plain and sea, the vibration of the tiny wings, the fading sound.”

Movement dominates this sequence. Grierson wrote of Basil Wright that he “is almost exclusively interested in movement and will build up movement in a fury of design and nuances of design; and for those whose eye is sufficiently trained and sufficiently fine, will convey emotion in a thousand variations on a simple theme. The quality of Wright’s sense of movement and of his patterns are distinctly his own and recognisably delicate. As with good painters, there is character in his line, and attitude in his composition. There is an overtone in his work which makes his descriptions uniquely memorable.”

As Greene observed, the second part, The Virgin Island, “is transitional, leading us away from the religious theme by way of the ordinary routine of living to industry.” This part includes a breath-taking montage of activities relating to daily life. Wright’s subjects pursue their activities and exchange banter with an extraordinary degree of naturalness, no doubt due to Wendt’s presence on location.

“In the third part, The Voice of Commerce,” Greene adds, “the commentary, which has been ingeniously drawn from a seventeenth-century traveller’s account of the island, gives way to scraps of business talk. As the natives follow the old ways of farming, climbing the palm or guiding their elephants’ foreheads against the trees they have to fell, voices dictate the bills of lading, close deals over the telephone, announce through loud-speakers the latest market prices.”

Good as it is, Greene’s description doesn’t quite convey the experimental nature of this part of the documentary. The GPO Film Unit had recently acquired its own sound equipment, and Grierson grasped the opportunity to demonstrate his belief that the soundtrack need not simply provide the obvious accompaniment in narration and music, but could make an individual contribution.

Grierson wrote of the “sound imagery” he discovered, which is used to such good effect in Song of Ceylon: “A curious fact emerges – your aeroplane noise may become not the image of an aeroplane but the image of distance or height. I cannot tell how far this imagery will go because we are only beginning to become dramatically and poetically conscious of sounds. The whole power of sound imagery will come as more and more sounds are detached and matured into special significance, which I believe is latent in them. This is not silent film with sound added. It is an art – the art of sound film.”

In his seminal book, Nature of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (1961), Siegfried Kracauer pays particular attention to this part of Song ofCeylon. “This beautiful documentary about Sinhalese life,” wrote Kracauer, “includes a montage sequence which tries to epitomise the impact of Western civilization on native custom. European voices from the London Stock Exchange, shipping agencies, and business offices form a crisscross pattern of sounds which is synchronised with shots illustrating the actual spread of industrialisation and its consequences for a pre-industrial population . . . This sequence has the character of a construction; intellectual argument prevails over visual observation. Yet the whole sequence is embedded in passages featuring camera-reality. Thus it acquires traits of an interlude. And as such it deepens the impression of cinematic life around it.”

It was once said of Grierson and his team at the GPO Film Unit that they were “not paid to tell the truth but to make people use the parcel post.” Unfortunately the lyrical beauty of Song of Ceylon sometimes does, in fact, obscure its social dimension. Yet, as Paul Rotha argued in Documentary Diary (1972), the film “carried implicit but nevertheless significant comment on the low industrial status of native labour in that Island.”

Of the last part of the film, The Apparel of a God, Graham Greene wrote that it “returns by way of the gaudy images of the mountain, to a solitary man laying his offering at Buddha’s feet, and closes again with the huge revolving leaves, so that all we have seen of devotion and dance, the bird’s flight and the gentle communal life of harvest, seems sealed away from us between the fans of foliage. We are left outside with the bills of lading and the loud-speakers.”

Song of Ceylon received the first prize at the 1935 Brussels International Film Festival – mainly for its imaginative use of sound, which was far in advance of contemporary achievement. Its standing among the film critics of the era was such that Roger Manvell in his book Film (1944) rated it as “possibly the greatest British-produced film in any category up to 1935, and for unsustained beauty probably unequalled anywhere outside Russia.”

Despite its critical acclaim, Song of Ceylon was not always popular with audiences. As Manvell stated, “Its elaboration, its marriage of sight and sound in such a way as to produce in a sensitive audience perspectives of meaning not ostensibly present in either image or sound-track alone, its length, its occasional under-exposed photography, did not always lead to a sympathetic reception. In other words it suffered from the courageous overlay of genius.”

Wright recognised the worth of Song of Ceylon. “That’s the only film of mine that I can sit through today without blushing or wanting to run out,” he said in the Mosquito interview, and ended his account of the making of the documentary with the perfect understatement: “The film just grew. It’s like that in film work.”

The director added a tribute to Lionel Wendt, who had died in 1944. “Without him I don’t think Song of Ceylon would have been what it is. For here was a man who knew Ceylon as few men did, and he was in touch with the avant-garde cinema of those days and he knew what the documentary people were doing. As a matter of fact, the only two people I met in Ceylon who knew anything about film then were Wendt and the artist George Keyt.”

Wendt’s working relationship with Wright didn’t cease with Song of Ceylon. Planning to start a film unit in Ceylon, Wendt returned to England to gain experience as an assistant director at Wright’s production company, Realist Films, which had been set up in 1937. In the end, however, he worked on only two productions. “The climate was getting him down,” Wright recalled, “and I could see that he was always longing to get back to Ceylon.”

Another classic Basil Wright documentary of the 1930s was Night Mail (1936), which Wright co-directed with Harry Watt. Night Mail, as with Song of Ceylon, featured an array of experimental sound techniques, such as a poem by W. H. Auden. This was followed by the less impressive Children at School (1937) and The Face of Scotland (1938). In 1945, Wright was appointed supervising producer at the GPO Film Unit, which had been renamed the Crown Film Unit at the beginning of World War Two.

Although Wright became an administrator, he did direct several other remarkable documentaries, such as The Waters of Time (1950), a study of the River Thames, World without End (1953), a UNESCO film directed in Mexico by Paul Rotha and in Thailand by Wright, and Immortal Land (1958), about the glories of Greece. In 1965, he was invited to return to the island to help rescue the Ceylon Government Film Unit (GFU). The GFU had been set up at independence in 1948 with equipment left behind by the British armed forces. As there was a dearth of local film-makers, foreign directors and technicians were employed in the early years, including Ralph Keene, who belonged to the second wave of English documentary-makers and had directed such films as New Britain (1940), Crofters (1944) and Cyprus is an Island (1946). During his stay on the island Keene made the influential Heritage of Lanka (1952) and Nelungama (1953). However, he and the others were on short-term contracts, so that by the early 1950s the GFU was staffed entirely by Ceylonese.

During the next ten years or so the Ceylonese directors at the GFU made some excellent films, such as George Wickremasinghe’sFishermen of Negombo(1953) and Order of theYellow Robe (1953), PragnasomaHettiarachchi’sArt and Architecture of Ceylon (1956), Makers, Motifs and Materials (1958), and Rhythms of the People (1959), and In the Steps of the Buddha (1962), and Irwin Dassanaike’sThe Living Wild (1959). By the mid-1960s, though, the GFU had reached a state of creative stagnation. Wright expressed willingness to help out, as the following letter he wrote at the time to George Wickremasinghe indicates:

“The length of my stay in Ceylon would, as I say, depend on the size and scope of the film or films to be made . . . As regards technical assistance, I have the impression that you have a well-equipped and experienced Unit, members of which I would be glad to work with. If however you have any staffing problems I could no doubt, given enough warning, bring my own cameraman, but this would of course add considerably to the expense. For your information I prefer to work with a small unit on location – a cameraman, an assistant cameraman, and a combined assistant director/production manger.”

It is sad to relate that Wright never made his return to the island. As so often happens, bureaucratic indifference resulted in a consummate opportunity being squandered. Certainly the GFU never regained its former glory. Indeed today, due to the lack of archival and preservation facilities, many of the negatives of the classic films have disintegrated, and so significant social documents of the past have been lost.

In later life, Wright became a distinguished film teacher, which was how I first met him in August 1971 at a British Film Institute workshop titled “Realism: Theory and Practice,” and had the privilege of viewing Song of Ceylon in his company. Needless to say, the aesthetic brilliance of the film had an immediate impact on this young English film student. As I quizzed Wright about the fascinating island on the screen, I was blissfully unaware that I would make my first trip to Sri Lanka in just two years’ time, or that I would eventually settle down there.

But that, as they say, is another story.

I have written many articles concerning Song of Ceylon over the years. The first was published in the (Colombo) Sunday Observer, December 13, 1985, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the release of the film, and an extended version appeared in the same newspaper ten years later - December 3, 1995 - to celebrate the 60th anniversary. A photo-essay on the subject was published in Serendib, Vol.17 No.3, May-June 1998, and on October 31, 2004, another extended version appeared in the (Colombo) Sunday Times to celebrate the 70th anniversary. Finally, an edited version was published in HimalSouthasian, November 2009.

ඒ වගේ ම තමන්ගේ මුළු ජීවිත කාලය පුරා ම කළ නිර්මාණවල එකම තේමාවක විවිධ ස්වරූපයන් හෝ එකම ශෛලීය භාවිතයක් ආත්මය කොටගත් කලාකාරයොත් ඉන්නවා. සක්වාදාවල සිට මා මෙතෙක් ආ ගමන්මඟේ යම් සමරූපී බවක් ඇත්නම් ඒ පිළිබඳ මා සවිඥානකයි.