Date: 21/09/2007

In the decades after Independence, Sinhala drama, which was once relegated to the periphery of cultural life, emerged into the spotlight as a vibrant mode of artistic expression.

SINHALA drama, in common with most other contemporary art forms of Sri Lanka, occupies a bipolar universe characterized by a complex set of tensions and associations occurring between the traditional and the modern, the indigenous and the foreign, or in a Tagorean phrase, between the home and the world. This situation is in large measure the product of certain features that are peculiar to the culture and to the historical circumstances surrounding them. Among these, the most important factor has been the relatively low social status accorded to mimetic and performative arts. Until almost the beginning of this century, the theatrical arts were confined to the folk domain. And since folk theatre was tied to single texts or a cluster of specific texts concerning myth and legend, dramatic writing remained a virtually unknown craft in Sinhala society.

The roots of the Sinhala drama that succeeded the professional stage go back to exercises in translation and adaptation undertaken by the English-educated literati who were inspired by the example of modern Western drama. As in the case of most other Asian countries, there were in Sri Lanka groups of concerned individuals who wished to develop a drama that was both modern and yet accessible to an uninstructed audience. They hoped to achieve this end through the translation and adaptation of suitable Western plays. In Sri Lanka, the choice included Gogol, Chekhov and Moliere.

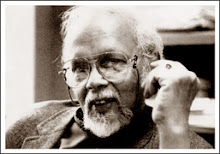

Ediriweera Sarachchandra

----------------------

By the 1950s, this approach appeared to have reached something of a dead end. The modes of realism and naturalism had failed to produce works of substance, and indeed continued to look and sound rather alien to the Sinhala stage. Sinhala drama seemed to have lost all sense of direction and purpose. It was at this point that Ediriweera Sarachchandra, Sri Lanka`s greatest playwright, came into the scene.

Sarachchandra, an academic by occupation, was a modernizer who was essentially Tagorean in spirit. Inde

ed, he had spent some of his formative years at Santiniketan and subscribed to the intercultural philosophy of Tagore. Sarachchandra, convinced that the direct emulation of Western forms was not the way forward for Sinhala drama, sought to attain a viable fusion of the Western and Asian modes. He further believed that drama was a poetic medium which, most properly, should concern itself with perennial themes, and not with quotidian issues. The use of poetry, music, song, dance and stylized gesture on the modern stage was entirely appropriate, he argued.

ed, he had spent some of his formative years at Santiniketan and subscribed to the intercultural philosophy of Tagore. Sarachchandra, convinced that the direct emulation of Western forms was not the way forward for Sinhala drama, sought to attain a viable fusion of the Western and Asian modes. He further believed that drama was a poetic medium which, most properly, should concern itself with perennial themes, and not with quotidian issues. The use of poetry, music, song, dance and stylized gesture on the modern stage was entirely appropriate, he argued.Maname

--------

Sarachchandra`s work for the stage followed these principles. Writing and directing the plays himself, he demonstrated outstanding poetic gifts and a sure grasp of modern stagecraft. Always working with `found material` such as Buddhist Jataka stories and folk tales, he experimented with traditional theatrical forms. For his path-breaking `Maname` (1956), Sarachchandra employed the almost extinct nadagam form. This turned out to be an inspired choice, for the nadagam elegantly accommodated the theatrical vocabulary he favored.

`Maname` accomplished several objectives. While offering an exceptionally satisfying theatrical experience, the play validated the path that Sarachchandra sought to follow. It demonstrated that a productive fusion of the traditional and the modern was not only feasible on stage but also desirable. As a shining example of new possibilities in theatre, `Maname` brought self-esteem and a mood of self-confidence into the sphere of Sinhala theatrical activity.

Over time, however, `Maname` and Sarachchandra`s subsequent dramatic output, along with his general philosophy of theatre, generated an adverse critique. It was argued that Sarachchandra`s kind of drama and the theatrical conventions he followed could neither reflect the actualities of contemporary society nor articulate thematic concerns of a social and political nature. It was also pointed out that Sarachchandra`s preoccupation with so-called `eternal values` deflected attention from the real and pressing issues of the day.

The view was also expressed that the use of song, music and stylized gesture could lead to unwholesome aesthetic indulgence on stage.

The controversy centering on Sarachchandra`s dramaturgy split the Sinhala theatre world into two camps. Although it failed to maintain a high level of understanding or historical knowledge, the debate was a necessary exercise - an evolutionary need, as it were - in a medium that was trying to define itself. However acrimonious at times, the exchanges had a salutary effect in the long run. They led to the realization that drama and theatre do not permit facile categorizations.

Notwithstanding the authoritative role played by Western models in Sinhala drama, the general movement or progression has been towards the consolidation of a presentation or performative mode of theatre as opposed to the representational. Examples of authentic realism are infrequent on the Sinhala stage, and naturalism is practically unknown.

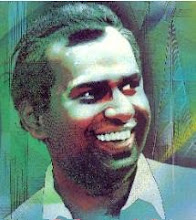

Gunasena Glalppatty

------------------

Gunasena Galappatty, was one of the greatest dramatists of Sri Lanka and his name is a legend among generations of Sinhala theatre goers. The work of a great life time has placed him among the immortals and has created for him a shrine in the world of Sri Lankan theatre. Galappatty

was the pioneer of suspense drama in Sri Lanka. After an academic and dramatic stint at University of Yale and Broadway in New York, Galappatty emerged in to the forefront, creating a tremendous impact by his dramatic technique of the harmonization of stylization with naturalism. His legendary production `Muduputtu` was a land mark of Sri Lankan drama and was created such a sensation that it became a controversial issue in the Sri Lankan theatre. Galappatty proved that traditional theatre style could be blended very effectively with western technique. `When he directed a play, he was almost in a trance. The atmosphere was like that within a temple. No one would dare to disturb, while a rehearsal was in progress`, one ardent follower of Galappatty stated.

was the pioneer of suspense drama in Sri Lanka. After an academic and dramatic stint at University of Yale and Broadway in New York, Galappatty emerged in to the forefront, creating a tremendous impact by his dramatic technique of the harmonization of stylization with naturalism. His legendary production `Muduputtu` was a land mark of Sri Lankan drama and was created such a sensation that it became a controversial issue in the Sri Lankan theatre. Galappatty proved that traditional theatre style could be blended very effectively with western technique. `When he directed a play, he was almost in a trance. The atmosphere was like that within a temple. No one would dare to disturb, while a rehearsal was in progress`, one ardent follower of Galappatty stated.After his first professional production `Sandakinduru`, Galappatty was awarded a Full-Bright scholarship. Galappatty was the first ever Sri Lankan to study professional theatrical work at Broadway and had the rare opportunity to experiment European stagecraft at the `Method School`, an American offshoot of Stanislavisky acting stylization.

At Broadway, Galappatty started abandoning operatic form of Sri Lankan folk drama and laid foundation on a novel and experimental style blending Western and traditional Sri Lankan theatre.

The profile of Sinhala drama changed radically within a decade of Independence. Over the decades, a medium once relegated to the periphery of cultural life emerged into the spotlight as a sinewy and vibrant mode of artistic expression. The dissonances between tradition and modernity continue to persist on the Sinhala stage despite its eclectic and liberal approach to the craft. Perhaps these can never be fully resolved, given that drama cannot fail to mirror social and cultural conflict.

No comments:

Post a Comment